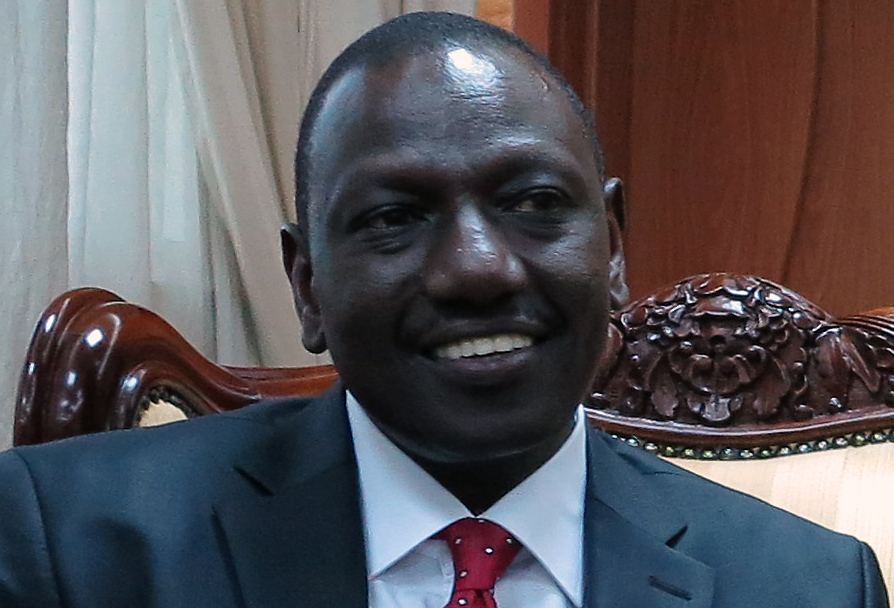

When President William Ruto announced sweeping PAYE relief for low and middle-income earners on Tuesday, the message was framed as immediate relief for Kenyan households. But coming on the same day the banking sector publicly warned that economic pressure remains acute where most businesses operate, the announcement also marks a deeper shift in how economic recovery is being approached.

Under the new measures, Kenyans earning up to Sh30,000 a month will no longer pay Pay As You Earn (PAYE) tax, while those earning up to Sh50,000 will see their PAYE rate reduced to 25 percent from 35 percent. The changes target income bands that economists describe as the “consumption engine” of the economy.

Hours earlier, Raimond Molenje, the Chief Executive Officer of the Kenya Bankers Association had publicly articulated the same pressure point, albeit from the perspective of lenders and businesses.

“Our macroeconomic indicators look strong, but challenges persist at the micro level, where 95 percent of businesses operate,” the KBA CEO said. “This is why we are proposing a 5 percent reduction in PAYE across all existing tax bands, along with a cap at 30 percent, to restore purchasing power and generate employment in productive sectors such as agriculture and manufacturing.”

The convergence of the two positions highlights a growing consensus: Kenya’s next phase of economic recovery will be judged less by stability indicators and more by whether households and small businesses can breathe again.

The Household Squeeze Beneath the Headline Numbers

Over the past year, Kenya has recorded improvements in inflation trends and relative currency stability. Yet for many workers, especially those earning below Sh50,000, the cost of living has continued to outpace income growth.

For Grace Mwangi, a retail supervisor in Nairobi earning Sh42,000 a month, the PAYE cut translates into several thousand shillings in additional take-home pay. “It may not sound like much, but it’s the difference between borrowing mid-month and finishing the month okay,” she said. “Most of it will go straight to food and transport.”

Economists say this is precisely why PAYE has become a focal point of policy debate.

“Low and middle-income earners spend almost all their income,” said an independent fiscal policy analyst. “When you tax them heavily, demand collapses quickly. When you give them relief, the money moves almost immediately through the economy.”

That movement matters most to micro and small enterprises, which dominate Kenya’s business landscape. According to official data, SMEs account for the vast majority of enterprises and a significant share of employment, but remain highly vulnerable to demand shocks.

Why Bankers Are Paying Attention

The banking sector’s intervention is notable not just for what it proposes, but for why it is speaking out now.

Banks sit at the intersection of household income, business performance, and government policy. Rising defaults, slower SME turnover, and subdued borrowing demand are often visible to lenders long before they show up in national statistics.

“When households struggle, SMEs struggle. When SMEs struggle, credit quality deteriorates,” said a senior banking executive who asked not to be named. “From a lender’s point of view, restoring purchasing power is a risk management issue as much as a growth issue.”

The KBA’s call for a broader PAYE reduction and a 30 percent cap reflects concern that while targeted relief is helpful, sustained recovery may require deeper tax reform to unlock productivity and employment across sectors.

Agriculture and Manufacturing: The Employment Logic

Both the government’s announcement and the banking sector’s proposal emphasise job creation, particularly in agriculture and manufacturing.

These sectors are labour-intensive and highly sensitive to domestic demand. When households spend more, farmers sell more produce, processors increase output, and factories add shifts or workers.

“Services respond quickly to consumption, but manufacturing and agriculture absorb labour at scale,” explained an industrial policy expert. “If demand rises without supply constraints, these sectors can drive more inclusive growth.”

However, analysts caution that PAYE relief alone will not be enough. Structural issues such as energy costs, logistics, access to affordable credit, and policy consistency will determine whether increased demand translates into sustained employment.

Fiscal Trade-Offs and Policy Direction

From a public finance perspective, the PAYE relief represents a trade-off. In the short term, government revenue from income tax is likely to decline. The policy bet is that higher consumption and economic activity will partially offset this through indirect taxes and broader growth.

“This is a shift from extraction to stimulation,” said a public finance expert. “The question is whether it becomes a one-off adjustment or part of a longer-term rebalancing of the tax system.”

The contrast between the government’s targeted relief and the banking sector’s broader proposal illustrates the tension between fiscal caution and economic urgency. Governments tend to move incrementally, while businesses often push for faster, wider reform.

What Success Will Look Like

Whether the policy shift delivers results will become clearer over the coming months.

Key indicators to watch include:

- Household consumption trends

- SME sales and employment levels

- Credit demand and repayment behaviour

- Manufacturing output and agricultural activity

- Overall tax revenue performance

For now, the same-day alignment between government action and private sector warning suggests a recalibration is underway. Economic strength will no longer be assessed solely through national indicators, but through the lived realities of households and the small businesses that sustain them.

As one economist put it: “Macroeconomic stability is necessary. But without microeconomic relief, it is not sufficient.”

Interesting …